© 2000-2023 - Enkey Magazine - All rights reserved

ENKEY SNC - VAT ID IT03202450924 / REA Code CA253701 - Phone. 078162719

To those who were born in the ’80s, space mice reads as Biker Mice from Mars, the iconic cartoon about motorbiking alien rodents fighting against the forces of evil. However, the space mice we’re talking about are something else entirely.

University of Yamanash, in Japan, announced the birth of 168 pups from eggs fertilized by sperm cells that were stored on the International Space Station for the best part of six years.

This is but one of the many science projects run on the ISS – but results, this time, far exceeded the scientists expectations.

A revolutionary blend of freeze-drying and chryogenics

Professor Wakayama Teruhiko and his team of researchers began the study on the “space mice” several years ago. The goal was finding out how cosmic radiations could affect the mice sperm cells stored on the ISS.

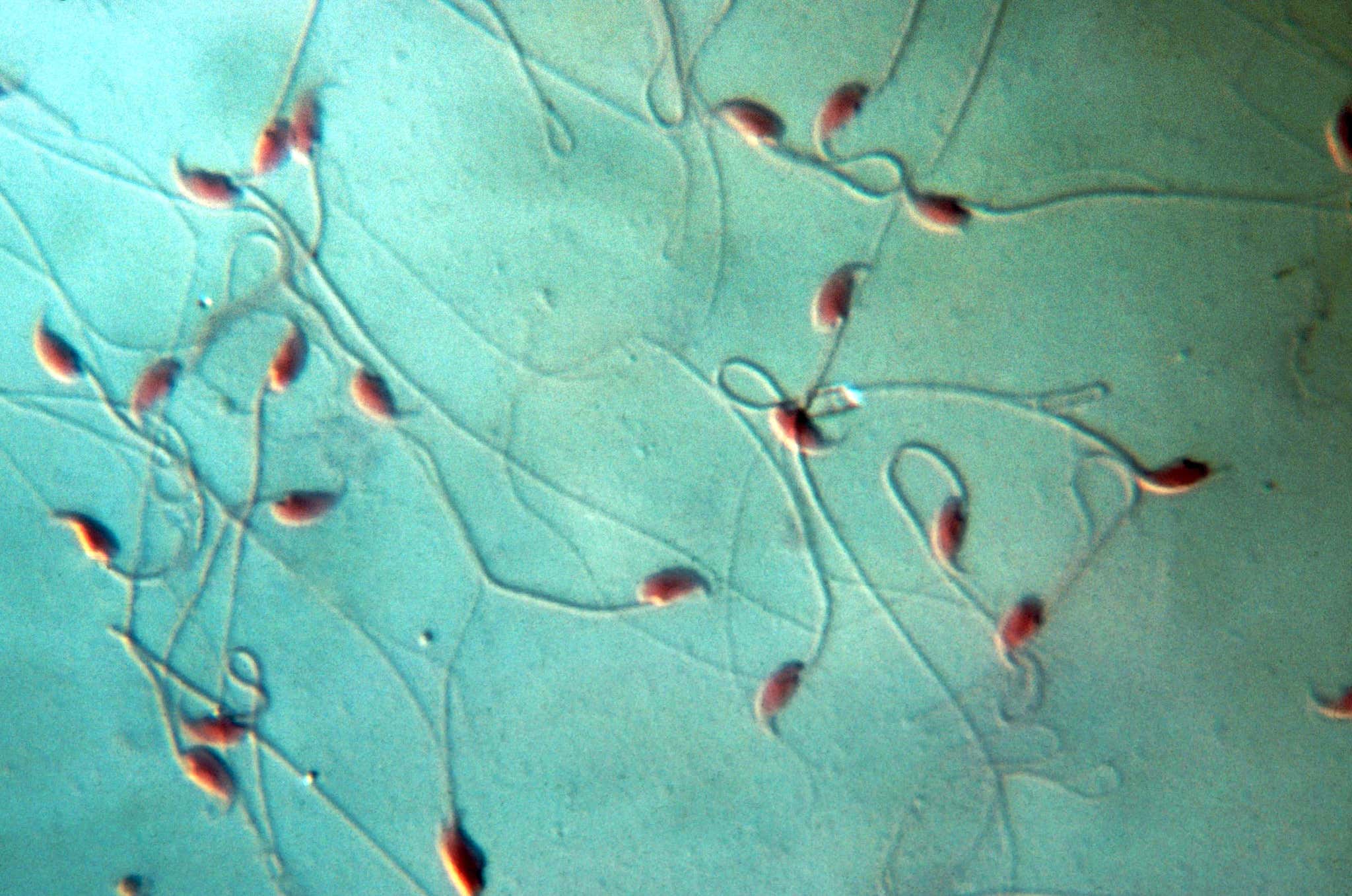

There were some logistical issues to address. Sperm, like water, can’t keep liquid form in space. The sperm cells had to be freeze-dried before being taken aboard the International Space Station. The next challenge was how to preserve the live sperm cells throughout the course of the experiment, which was slated to last a good six years.

Japan scientists implemented an innovative combination of freeze-drying and chryogenics to ensure that the sperm cells would not die ahead of time. The freeze-dryed sperm was artificially hibernated and preserved at ultra-low temperatures on the ISS-

But would the sperm cells still be fertile upon returning on Earth? The next step was using them to fertilize mice eggs in a dish. This resulted in the birth of 168 pups that were promptly nicknamed “space mice” – but, as we’ll see, don’t appear to be any different from their Earth-born cousins.

How the “space mice” were born

The experiment first began in 2013. University of Yamanash had selected champions of sperm from twelve lab mice. The sperm cells were later sorted in eighty-four test tubes that would spend varying lengths of time on board of the International Space Station.

A first batch of test tubes would spend nine months in space – roughly the equivalent of a human pregnancy. The sperm, once retrieved, showed signs of slight DNA damage but could still be used to fertilize the eggs.

A second tranche of sperm cells would remain in space for as much as two years and nine months. Finally, the last batch spent a good six years on the International Space Station.

Samples from all three batches gave birth to a progeny of “space mice” that appeared hale and in good health from the get-go. If we are to believe what the exams say, the “Biker Mice from ISS” don’t show any significant difference from ordinary litters bred on Earth. The prolonged stay in space did not affect the fertility of sperm cells and even the ratio of males and females births among the newborn matched the percentages of “normal” litters.

But there is more. The result of the experiment proved that sperm cells might survive in space for even greater length of time. The team of Professor Teruhiko have theorized that freeze-dried sperm could very well be safely preserved in space even for as long as two hundred year.

The goals of researching space mice

But wait – you might ask – what is the purpose of an experiment with freeze-dried sperm, eggs in a dish and space mice? What was all the ado for?

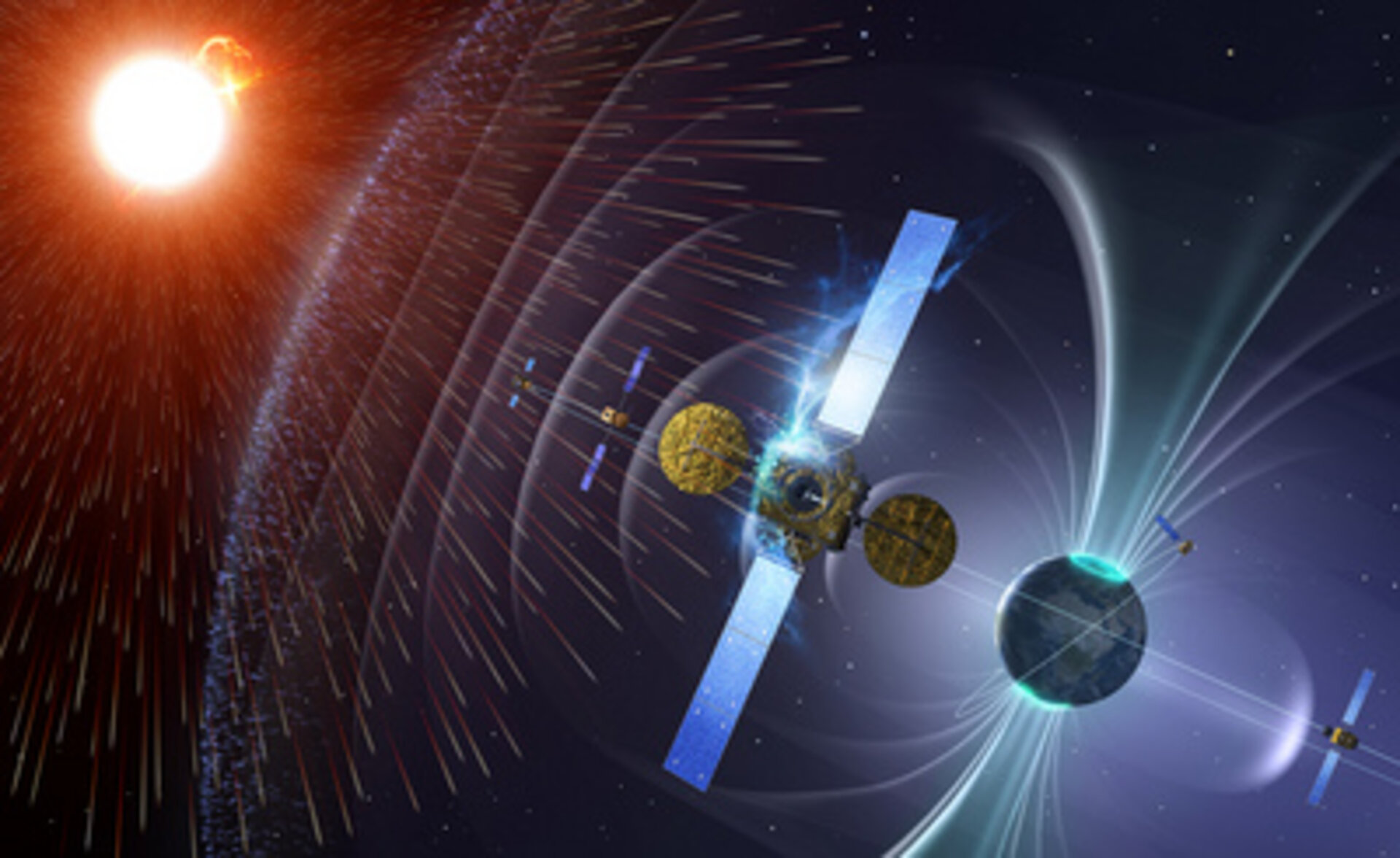

The purpose of the research was to investigate how cosmic radiations could affect sperm, and most importantly, the effects that a prolonged stay in space would have on its fertility. The International Space Station is constantly exposed to radioactive levels far superior to thos that affect our planet. And the intensity of radiations only increases further outside Earth’s magnetic field.

Investigating the short, middle and long-term effects of radiation exposure on fertility is a challenge that influence the future of mankind.

Space exploration is, after all, the first step toward the colonization of other planets in the Solar System. Such is the aim of the ever-increasing lunar missions; you can find out more about how ESA joined the “Moon Rush” here. The colonization of Mars may be also an option, and many already consider our neighbor planet as something akin to a “New World“.

But in order to bring life on other planets, science must first analyze the effects of cosmic radiations on the human body. A thorough evaluation of all the risk factors involved, and the subsequent development of safety measures, is necessary if men and women of the future are to travel in space. The birth of space mice paves the way for new fields of research and takes us yet another step closer to conquering the stars.

This post is also available in:

Italiano

Italiano